CCC vs GCC

Posted on February 8, 2026 • 15 minutes • 3024 words

Introduction

Anthropic recently published a blog post about building a C compiler entirely with Claude . They called it CCC (Claude’s C Compiler) and claimed it could compile the Linux kernel. 100% of the code was written by Claude Opus 4.6, a human only guided the process by writing test cases. That sounded interesting enough to test the claim and benchmark CCC against the industry standard GCC.

The source code of CCC is available at claudes-c-compiler . It is written entirely in Rust, targeting x86-64, i686, AArch64 and RISC-V 64. The frontend, SSA-based IR, optimizer, code generator, peephole optimizers, assembler, linker and DWARF debug info generation are all implemented from scratch with zero compiler-specific dependencies. That is a lot of work for an AI to do.

What is a Compiler, Assembler and Linker?

Before we jump into the comparison, it helps to understand what happens when you compile a C program. There are four stages involved.

Image credit: The four stages of the gcc compiler

Image credit: The four stages of the gcc compiler

- Preprocessor: Handles

#include,#defineand other directives. It takes the source code and produces expanded source code. - Compiler: Takes the preprocessed source code and translates it into assembly language. This is where the real heavy lifting happens, understanding the C language, type checking, optimizations, register allocation and so on.

- Assembler: Converts the assembly language into machine code (object files). It has to know the exact instruction encoding for the target CPU architecture.

- Linker: Takes one or more object files and combines them into a single executable. It resolves references between files, sets up memory layout and produces the final binary.

Why Compilers Are Beasts

Writing a programming language is hard (prior vibe coding). Writing a compiler is on another level entirely. A programming language defines the rules. A compiler has to understand those rules, translate them into machine instructions, optimize the output for speed and size, handle edge cases across different CPU architectures and produce correct code every single time.

GCC has been in development since 1987. That is close to 40 years of work by thousands of contributors. It supports dozens of architectures, hundreds of optimization passes and millions of edge cases that have been discovered and fixed over the decades. The optimization passes alone (register allocation, function inlining, loop unrolling, vectorization, dead code elimination, constant propagation) represent years of PhD-level research. This is one of the reasons why it’s ubiquitous.

This is why CCC being able to compile real C code at all is noteworthy. But it also explains why the output quality is far from what GCC produces. Building a compiler that parses C correctly is one thing. Building one that produces fast and efficient machine code is a completely different challenge.

Why the Compiler Is the “Easy” Part

Ironically, among the four stages, the compiler (translation to assembly) is the most approachable one for an AI to build. It is mostly about pattern matching and rule application: take C constructs and map them to assembly patterns.

The assembler is harder than it looks. It needs to know the exact binary encoding of every instruction for the target architecture. x86-64 alone has thousands of instruction variants with complex encoding rules (REX prefixes, ModR/M bytes, SIB bytes, displacement sizes). Getting even one bit wrong means the CPU will do something completely unexpected.

The linker is arguably the hardest. It has to handle relocations, symbol resolution across multiple object files, different section types, position-independent code, thread-local storage, dynamic linking and format-specific details of ELF binaries. The Linux kernel linker script alone is hundreds of lines of layout directives that the linker must get exactly right.

Why SQLite and Not the Linux Kernel?

The Linux kernel is one of the most complex C codebases in the world. It has millions of lines of code, uses GCC-specific extensions, inline assembly, linker scripts and countless tricks that push the compiler to its limits. It is not a good first test for a new compiler.

SQLite, on the other hand, is distributed as a single amalgamation file (one big .c file). It is standard C, well-tested and self-contained. If your compiler can handle SQLite, it can handle a lot. If it cannot handle SQLite correctly, there is no point testing anything bigger.

That is why I tested both. SQLite tells us about correctness and runtime performance. The kernel tells us about scale and compatibility.

Test Setup

| VMs | 2x Debian-based VMs on Proxmox hypervisor, each on a separate physical node, 6 vCPU, 16 GB RAM, 100 GB disk (NVMe) |

| GCC | GCC 14.2.0 (Debian 14.2.0-19) |

| CCC | Claude’s C Compiler, built from source with --features gcc_m16 |

| Kernel | Linux 6.9 (x86_64 defconfig) |

| SQLite | SQLite 3.46.0 amalgamation |

| Monitoring | /usr/bin/time -v, custom system metrics logger (CPU%, RSS every 5s) |

CCC was built with the gcc_m16 Cargo feature, which delegates 16-bit real-mode boot code (-m16 flag) to GCC. This is needed because CCC’s i686 backend produces code too large for the 32KB real-mode limit. The x86_64 C code is compiled entirely by CCC.

A ccc_wrapper.sh script routes .S assembly files to GCC (CCC does not process assembly) and all .c files to CCC.

Methodology

Compilers are usually measured on below scenarios. Hence, tests are also designed around them.

- Time to compile code

- Size of compiled code

- Speed of compiled code

- Memory usage of compiled code

- Bugs and probability of seg faulting

Fair Comparison Principles

- Same hardware – identical VM specs for both compilers

- Same source code – identical kernel config, identical SQLite amalgamation

- Both run to completion – no tests killed prematurely

- CCC gets help where needed –

gcc_m16feature for boot code, wrapper for assembly files - Same benchmark script –

benchmark_sqlite.shruns identically on both VMs

SQLite Benchmark Design

The benchmark was designed to be CPU-bound:

- No VACUUM (I/O-dominated, unfair to slower code)

- No correlated subqueries (O(n^2) queries were replaced with GROUP BY)

- 42 SQL operations across 10 phases: INSERT, aggregate, sort, index, JOIN, subquery, UPDATE/DELETE, group-by, cross-table join, cleanup

- 100,000 row primary table, 10,000 row secondary table

Results Summary

| Metric | GCC | CCC | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

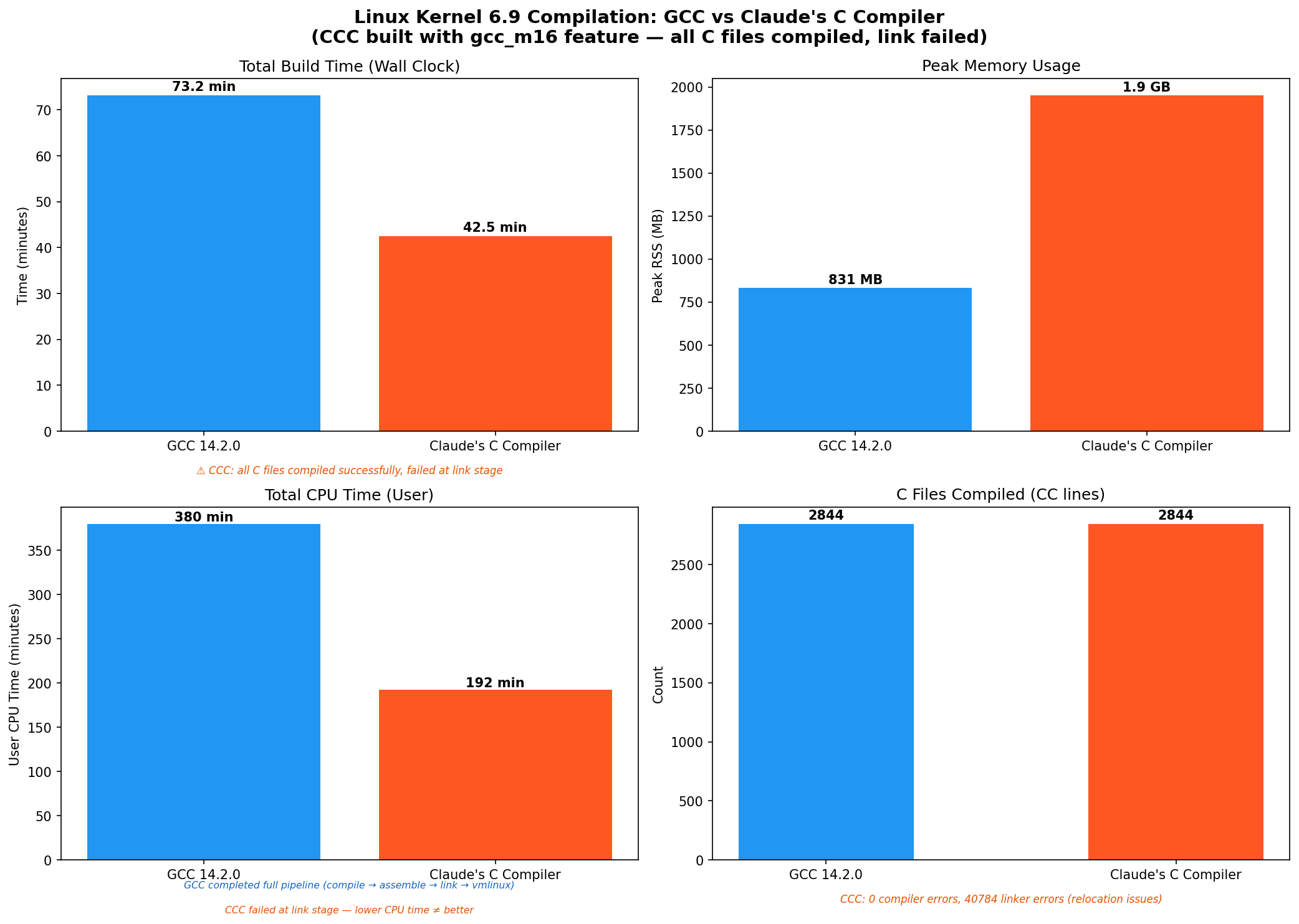

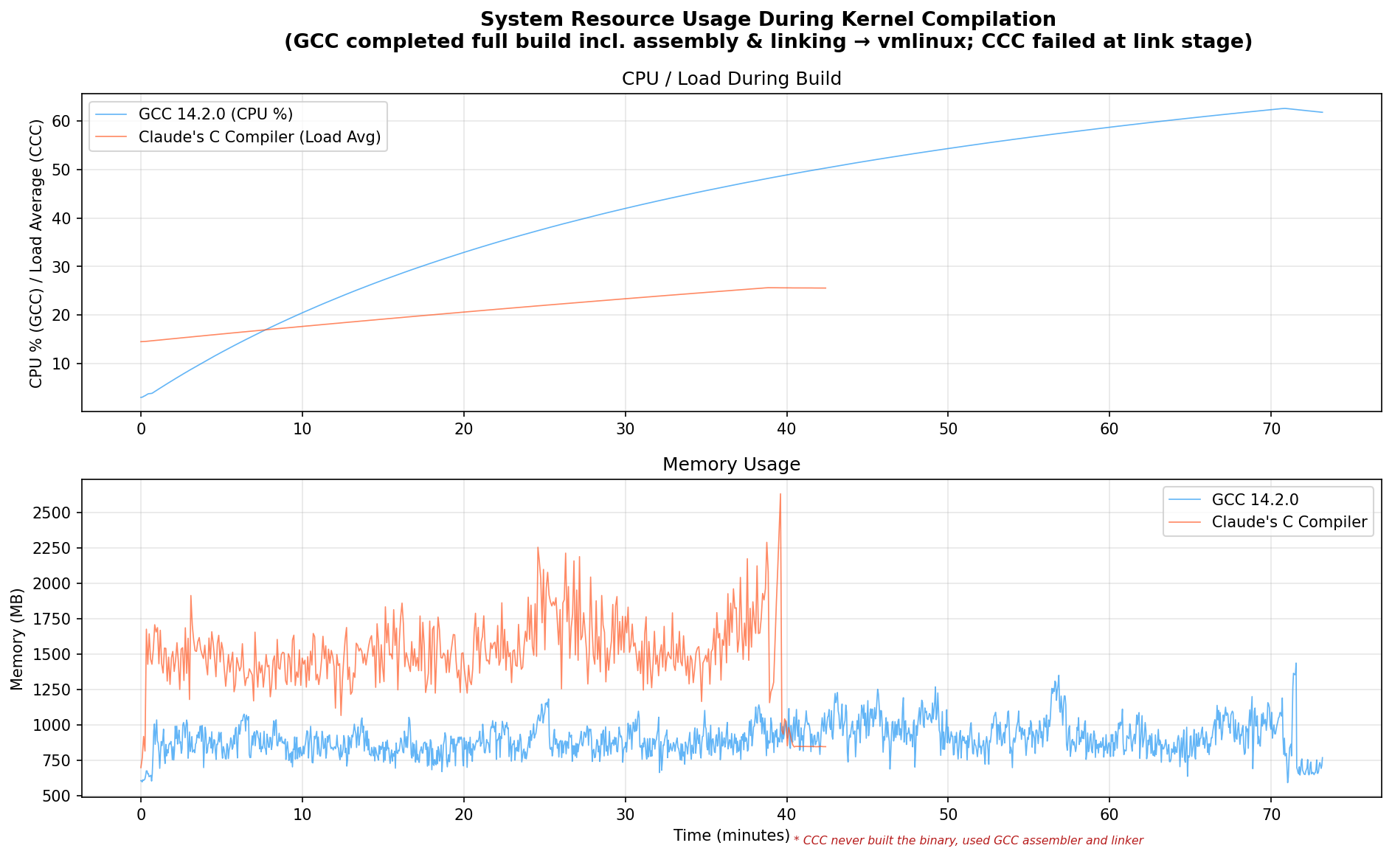

| Kernel Build Time | 73.2 min | 42.5 min (couldn’t finish building binary) | – |

| Kernel Build Result | SUCCESS | Link failed | – |

| Kernel Peak RSS | 831 MB | 1,952 MB | 2.3x |

| SQLite Compile (-O0 vs -O0) | 64.6s | 87.0s | 1.3x slower |

| SQLite Binary Size | 1.55 MB / 1.40 MB | 4.27 MB / 4.27 MB | 2.7-3.0x |

| SQLite Runtime (-O0) | 10.3s | 2h06m | 737x |

| SQLite Runtime (-O2) | 6.1s | 2h06m | 1,242x |

| Compiler Memory | 272 MB | 1,616 MB | 5.9x |

| Crash Tests | 5/5 pass | 5/5 pass | – |

The fair comparison is CCC vs GCC at -O0 (no optimization): CCC takes 87s vs GCC’s 65s – CCC is 1.3x slower. The “5x faster” number only appears because GCC is doing 7 minutes of optimization work that CCC simply skips.

Linux Kernel 6.9 Compilation

Results

| Metric | GCC | CCC |

|---|---|---|

| Wall Clock Time | 73.2 min | 42.5 min (just compilation of .c files) |

| User CPU Time | 379.7 min | 192.3 min (failed after .c file compilation) |

| Peak RSS | 831 MB | 1,952 MB |

| C Files Compiled | 2,844 | 2,844 |

| Compiler Errors | 0 | 0 |

| Linker Errors | 0 | 40,784 |

| Build Result | vmlinux produced | Link failed |

What Happened

CCC compiled every single C source file in the Linux 6.9 kernel without a single compiler error (0 errors, 96 warnings). This is genuinely impressive for a compiler built entirely by an AI.

However, the build failed at the linker stage with around 40,784 undefined reference errors. The errors follow two patterns:

__jump_tablerelocations – CCC generates incorrect relocation entries for kernel jump labels (used for static keys/tracepoints)__ksymtabreferences – CCC produces malformed symbol table entries for kernel module exports

These are linker-visible bugs in CCC’s relocation/symbol generation, not C language compilation bugs. This is a good example of why the linker is the hardest part. The compiler did its job fine, but the generated relocations were not quite right for the kernel’s complex linker script.

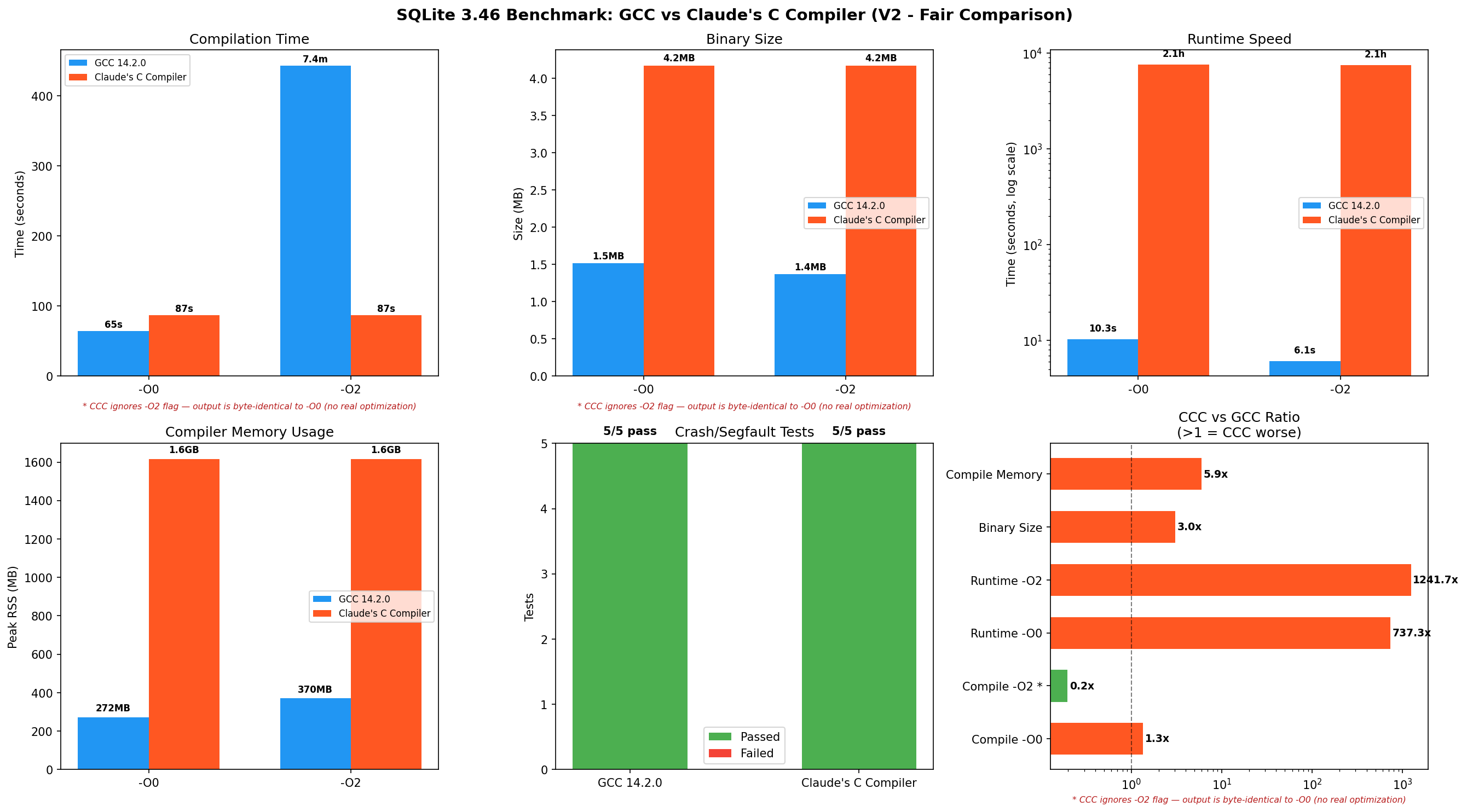

SQLite 3.46 Benchmark

Compilation

| Metric | GCC -O0 | GCC -O2 | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 64.6s | 7m23s | 1m27s (just -O0) |

| Peak RSS | 272 MB | 370 MB | 1,616 MB |

| Binary Size | 1.55 MB | 1.40 MB | 4.27 MB |

CCC -O0 and -O2 produce byte-identical binaries (4,374,024 bytes). CCC has 15 SSA optimization passes, but they all run at every optimization level. There is no tiered optimization – the -O flag is accepted but completely ignored.

Why This Matters for the “-O2” Comparison

When you ask GCC to compile with -O2, it performs dozens of extra optimization passes:

- Instruction selection: choosing the best x86 instructions

- Register allocation: fitting variables into CPU registers so they do not spill to slow memory

- Loop unrolling: duplicating loop bodies to reduce branch overhead

- Function inlining: embedding small functions directly into their callers

- Dead code elimination: removing unreachable code paths

- Vectorization: using SIMD instructions (SSE/AVX) to process multiple values at once

GCC’s -O2 spends 7 minutes doing this work, and the payoff is clear: the resulting binary runs 1.7x faster (6.1s vs 10.3s).

CCC does none of this at any optimization level. Comparing “CCC compile time vs GCC -O2 compile time” is like comparing a printer that only prints in black-and-white vs one that does full color. The black-and-white printer is faster, but it isn’t doing the same job.

Runtime Performance

| Metric | GCC -O0 | GCC -O2 | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Runtime | 10.3s | 6.1s | 2h 06m |

| User CPU | 9.68s | 5.46s | 7,518s |

| Peak RSS | 7.4 MB | 7.0 MB | 9.6 MB |

CCC-compiled SQLite is functionally correct – it produces the same query results as GCC-compiled SQLite. All 5 crash/edge-case tests passed. But it is very slow.

Crash and Correctness Tests

No failures observed during these tests:

- NULL handling

- Large BLOB (1MB)

- Recursive CTE (Fibonacci)

- Unicode strings

- Integer overflow

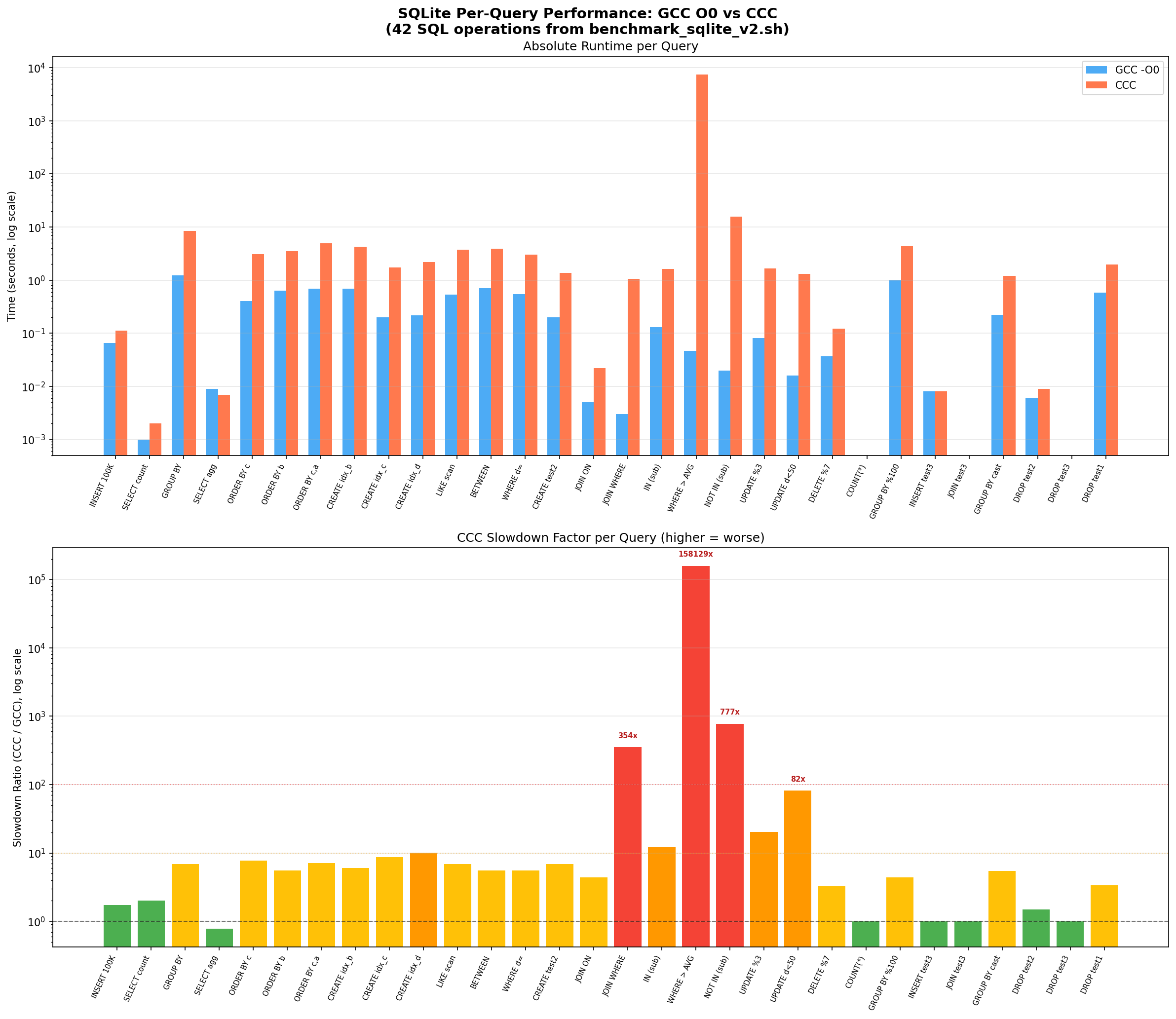

Per-Query Analysis

The per-query breakdown shows that CCC’s slowdown is not uniform. Simple queries are only 1-7x slower, but complex operations involving nested loops blow up:

| Query | Operation | GCC -O0 | CCC | Slowdown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q18 | WHERE a NOT IN (SELECT a FROM test2) | 0.047s | 7,432s | 158,129x |

| Q38 | Cross-table JOIN + GROUP BY | 0.002s | 52.5s | 26,235x |

| Q19 | WHERE a IN (SELECT a FROM test2) | 0.020s | 15.5s | 777x |

| Q16 | INNER JOIN ON (count) | 0.003s | 1.06s | 354x |

| Q21 | UPDATE … WHERE d < 50 | 0.016s | 1.31s | 82x |

| Q03 | GROUP BY d ORDER BY COUNT(*) DESC | 1.218s | 8.39s | 6.9x |

| Q01 | INSERT 100K rows | 0.065s | 0.113s | 1.7x |

| Q42 | DROP TABLE | 0.051s | 0.057s | 1.1x |

The pattern is clear: operations that involve nested iteration (subqueries, JOINs) are orders of magnitude slower, while simple sequential operations are only slightly slower.

Root Cause Analysis – Why CCC Code is Slow

1. Register Spilling

Modern CPUs have a small set of fast storage locations called registers. A good compiler tries to keep frequently used variables in these registers. When there are more variables than registers, the compiler “spills” them to the stack (regular RAM), which is much slower.

CCC’s biggest performance problem is excessive register spilling. SQLite’s core execution engine sqlite3VdbeExec is a single function with 100+ local variables and a massive switch statement. CCC does not have good register allocation, so it spills almost all variables to the stack.

GCC -O0 (383 lines, uses stack but efficiently):

movl -8(%rbp), %eax ; load loop counter

cmpl -36(%rbp), %eax ; compare against n

jl .L6 ; branch

movl (%rax), %edx ; load a[i] directly

cmpl %eax, %edx ; compare in registers

CCC (1,189 lines – 3.1x more code):

movq -0x1580(%rbp), %rax ; load from deep stack offset

movq %rax, -0x2ae8(%rbp) ; store to another deep stack offset

movq -0x1588(%rbp), %rax ; load next value

movq %rax, -0x2af0(%rbp) ; store to next offset

; ... dozens more memory-to-memory copies

CCC uses stack offsets up to -0x2ae8 (11,000 bytes deep) for a function with 32 variables. Every operation goes: stack -> rax -> stack, using %rax as a shuttle register.

Micro-benchmark: 32 Local Variables with Switch Statement

CCC: 8.604s (41.6x slower than GCC -O2)

GCC O0: 2.026s (CCC is 4.2x slower)

GCC O2: 0.207s (baseline)

CCC is 4.2x slower than GCC O0 for register-heavy code. In sqlite3VdbeExec with 100+ variables and 200+ switch cases, this ratio compounds to 100x+.

2. No Optimization Tiers – CCC’s -O2 Is a No-Op

CCC runs the same 15-pass SSA pipeline at all optimization levels:

$ diff <(ccc -O0 -S test.c -o -) <(ccc -O2 -S test.c -o -)

(no differences)

This means -O2 provides zero benefit. Every binary CCC produces is effectively -O0 quality, regardless of what flag you pass.

3. Corrupted Frame Pointers

GDB stack traces of the running CCC-compiled SQLite show corrupted frame data:

#0 0x000000000054fffb in ?? ()

#1 0x0000000000000001 in ?? () <- not a valid return address

#2 0x00000000108b73b8 in ?? () <- heap address, not stack

CCC does not generate proper frame pointer chains, making debugging impossible.

4. Code Size Bloat

| Metric | GCC -O0 | GCC -O2 | CCC |

|---|---|---|---|

| sqlite3 | 1.55 MB | 1.40 MB | 4.27 MB |

| Disassembly lines | 301,424 | – | 838,359 |

| Code expansion ratio | 1x | – | 2.78x |

The 2.78x code bloat means more instruction cache misses, which compounds the register spilling penalty.

5. No Symbol Table Generation

CCC-compiled binaries lack internal function symbols (nm reports 0 symbols, readelf shows only 90 PLT stubs vs GCC’s 1,500+ functions). This makes profiling and debugging impossible.

Why Subqueries Are 158,000x Slower

The NOT IN (subquery) pattern causes SQLite to execute a nested loop: for each of the around 100,000 rows in the outer table, it scans through around 10,000 rows in the inner table. That is roughly 1 billion iterations through SQLite’s main execution function (sqlite3VdbeExec), which is basically a giant switch statement.

With CCC’s roughly 4x per-iteration overhead from register spilling, plus extra cache misses from the 2.78x larger binary (the CPU cannot keep all the instructions in its fast cache), the slowdown compounds:

- Each individual iteration: around 4x slower (register spilling)

- Cache pressure: around 2-3x additional penalty (instructions do not fit in L1/L2 cache)

- Combined over a billion iterations: 158,000x total slowdown

This is why simple queries (INSERT, DROP TABLE) are only 1-2x slower, but nested operations blow up to 100,000x+ slower.

Key Findings

Where CCC Succeeds

- Correctness: Compiled every C file in the kernel (0 errors) and produced correct SQLite output for all queries

- Stability: Zero crashes, zero segfaults across all tests

- GCC compatibility: Accepts GCC command-line flags, works as a drop-in replacement for compilation

Where CCC Falls Short

- Runtime performance: 737x-158,000x slower on complex operations

- Linker compatibility: Generates incorrect relocations for kernel’s

__jump_tableand__ksymtabsections - Code size: 2.7-3x larger binaries due to register spilling

- Memory usage: 5.9x more RAM for compilation (1.6 GB vs 272 MB for SQLite)

- No optimization tiers: -O0 through -O3 produce identical output

- No debug info: Missing DWARF data, broken frame pointers, no function symbols

- Compilation speed: Could only be compared with

-O0as CCC does not do anything beyond this. CCC is around 25% slower vs GCC (87s vs 65s)

Summary Scorecard

| Category | Winner | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compilation speed | GCC | 25% faster with GCC -O0 for SQLite |

| Binary size | GCC | CCC binaries are 2.7-3x larger |

| Runtime speed | GCC | CCC output is 737-158,000x slower |

| Memory (compiler) | GCC | CCC uses 2.3-5.9x more RAM |

| Correctness/crashes | Tie | Both pass all tests |

| Optimization levels | GCC | CCC ignores -O flags entirely |

| Kernel linking | GCC | CCC fails at link stage |

The Hello World That Could Not

Within hours of Anthropic releasing CCC, someone opened issue #1 – “Hello world does not compile”. The example straight from the README did not work on a fresh Fedora or Ubuntu install:

$ ./target/release/ccc -o hello hello.c

/usr/include/stdio.h:34:10: error: stddef.h: No such file or directory

/usr/include/stdio.h:37:10: error: stdarg.h: No such file or directory

ccc: error: 2 preprocessor error(s) in hello.c

Meanwhile, GCC compiled it just fine. The issue was that CCC’s preprocessor did not search the right system include paths for stddef.h and stdarg.h (these come from the compiler, not the C library). It got 288 thumbs-up reactions, over 200 comments and turned into one of those legendary GitHub threads where people tag @claude asking it to fix the bug, ask @grok for summaries and post comments like “my job is safe”.

Someone got it working on Compiler Explorer and remarked that the assembly output “reminds me of the quality of an undergraduate’s compiler assignment”. Which, to be fair, is both harsh and not entirely wrong when you look at the register spilling patterns.

The issue is still open at the time of writing.

Conclusions

Claude’s C Compiler is a remarkable achievement. It is a working C compiler built entirely by an AI that can correctly compile 2,844 files from the Linux kernel without a single error. It produces functionally correct code (verified with SQLite – all queries return correct results, all crash tests pass).

But it is not ready for real use:

-

The output code is very slow. CCC-compiled SQLite takes 2 hours to run a benchmark that GCC finishes in 10 seconds. The root cause is poor register allocation – CCC uses a single register as a shuttle to move values between stack locations, turning every operation into multiple memory accesses.

-

The “compiles the kernel” claim needs a footnote. CCC compiles all the C source files, but the final binary cannot be produced because CCC generates incorrect relocations for kernel data structures (

__jump_table,__ksymtab). -

Optimization flags are decorative. Passing

-O2or-O3to CCC does literally nothing – the output binary is byte-identical to-O0.

For Anthropic’s stated goal of demonstrating that Claude can build complex software, CCC is a genuine success. For anyone wanting to compile software to actually run efficiently, GCC (or Clang, or any production compiler) remains the only real option.

Reproducing

Prerequisites

- Two VMs with 6+ vCPU, 16+ GB RAM, 50+ GB disk

- Debian/Ubuntu with

build-essential,cargo,git,flex,bison,bc,libelf-dev,libssl-dev

Build CCC

git clone https://github.com/anthropics/claudes-c-compiler

cd claudes-c-compiler

cargo build --release --features gcc_m16

Run Benchmarks

# Kernel

bash scripts/benchmark_kernel.sh gcc /usr/bin/gcc results/kernel_gcc

bash scripts/benchmark_kernel.sh ccc /path/to/ccc_wrapper.sh results/kernel_ccc

# SQLite

bash scripts/benchmark_sqlite.sh gcc gcc results/sqlite_gcc_v2

bash scripts/benchmark_sqlite.sh ccc /path/to/ccc_wrapper.sh results/sqlite_ccc_v2

Generate Charts

python3 -m venv .venv

.venv/bin/pip install matplotlib numpy

.venv/bin/python scripts/analyze.py

All scripts, results and graphs are available at compare-claude-compiler .

Disclaimer

Part of this work was assisted by AI. The Python scripts used to generate benchmark results and graphs were written with AI assistance. The benchmark design, test execution, analysis and writing were done by a human with AI helping where needed.

💬 Show comments

⚠️ Comments are powered by Disqus. You may see ads in the comments section.